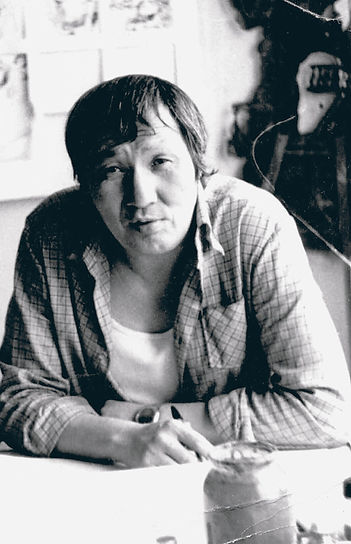

Adrian SAKHALTUEV

Adrian Sakhaltuev: On Art, Emigration, and Life at a Turning Point

The son of Radna Sakhaltuev, a legendary figure in Ukrainian animation and the art director behind iconic films such as "Adventures of Captain Vrungel", "Doctor Aybolit", and "Treasure Island", Adrian Sakhaltuev continues his family's legacy of artists and innovators — and today, he speaks with us about the most essential things.

In this candid conversation with Gregory Antimony, Adrian shares his personal story and reflections on the creative path, emigration, Russia’s war against Ukraine, and the transformation of the animation profession in the digital age.

📌 In this program:

-

The journey from a family of artists into Ukrainian and international animation

-

Why working in advertising taught him discipline

-

How he ended up in Canada — and what it means to be an “invisible” professional without local credentials

-

What artificial intelligence is doing to creative professions

-

Why “short format” is replacing meaning — and how to live with that

-

Reflections on his Ukrainian and Buryat roots, family heritage, cultural identity, and inner freedom

This conversation with Gregory Antimony is more than just an interview — it's a portrait of a generation caught between worlds, professions, and histories.

GREGORY: Hello, dear viewers. This is The Interview Hour. I’m Gregory Antimony, and today our guest is Adrian Sakhaltuev — artist, animator, producer, and director. Did I cover all your roles?

ADRIAN: I think so — for the most part.

GREGORY: Online you're often referred to as a Ukrainian director. Is that how you present yourself — or did it just happen that way? Do you truly feel like a Ukrainian director?

ADRIAN: Of course. Yes, absolutely. But first, let me thank you for the invitation — it’s a great honor for me to be here. And second — I do consider myself a Ukrainian director, because I’ve never really been anything else. All my films were made in Ukraine. There weren’t many of them — I mostly worked as an animator or commercial director — but everything I created as an author was born in Ukraine.

GREGORY: When I found out who your father was, I was pleasantly surprised — it turns out he was one of the pioneers of Ukrainian animation. Would it be fair to say he stood at the origins of this field in Ukraine?

ADRIAN: It might be too much to call him a founding father — there were others who started earlier. But yes, he was definitely a pioneer of Ukrainian animation. After the war, when the studio was founded, he joined in the early days and worked there until the very end of its existence.

GREGORY: When I read about Radna Filippovich and learned that he’s about to turn ninety…

ADRIAN: Yes, on May 15 — he’ll be ninety.

GREGORY: Exactly, and I immediately thought: of course his son would follow in his footsteps. But then I was surprised to see that you don’t really emphasize your professional path as a direct result of your father’s influence.

ADRIAN: Well, his influence was definitely there — mostly in the form of advice. But the actual choice of profession — that was my own. As a teenager, I had options — and I deliberately turned toward animation rather than, say, medicine. Though I admit, that probably sounds a bit unexpected.

GREGORY: Yeah, not exactly the typical path. But okay, the choice was made. You studied in Kyiv, right?

GREGORY: You received your education in Kyiv?

ADRIAN: Yes.

GREGORY: And then you started working at the... science... popular science studio?

ADRIAN: Yes, at Kyivnaukfilm, which by that time had already become Ukranimafilm. I started there as an animator, and later — while still working — I enrolled in university and completed my studies. Unfortunately, by the mid-90s, things started going downhill. They practically stopped producing animated films. And those few that were made — there were very few of them. So surviving in that environment became almost impossible. That’s when I started traveling — studying at the institute while also taking animation jobs abroad.

GREGORY: To Poland first?

ADRIAN: Yes, Poland was my first trip.

GREGORY: And how did it feel there? After all — it’s a completely different country, different atmosphere...

ADRIAN: Yes, at first it was a bit of a shock. That first trip abroad — to Poland — was a real cultural jolt. First of all, there was light everywhere. And in Kyiv at the time, we often had power outages. Secondly, the professional atmosphere was very pleasant — warm and welcoming. And the overall approach to work was somewhat different. Not radically, but noticeably so.

GREGORY: What do you mean by that?

ADRIAN: In Poland, for the first time, I encountered what we now call the pipeline — the production conveyor system that has become standard in animation studios. The Kyiv school was very strong back then. It produced amazing work, and Kyiv animation was well known — both in the Soviet Union and abroad. But the approach was more... artistic, I’d say. In Poland, everything was very structured: you had to do what was needed, not how you personally envisioned it.

GREGORY: In one of your interviews, you spoke about the balance between creativity and craft — in the context of your next destination: the United States. What did working in America give you?

ADRIAN: Training. Perspective. A new attitude toward the profession and animation in general. How it’s really done. That trip to the States was a turning point for me. I didn’t stay there very long, but it gave me a lot.

GREGORY: Well, it was six years, if I’m not mistaken?

ADRIAN: No, a bit less than that.

GREGORY: And how did you get there?

ADRIAN: I was invited to work as an animator at a studio. My teacher, Valeriy Konoplyov — who now lives in Los Angeles — recommended me to a producer. We got in touch back in the 90s — and I received a letter of invitation. I got my visa and went to work. I was twenty-three at the time.

GREGORY: But technically, you could have stayed? That option was on the table?

ADRIAN: I think — yes.

GREGORY: So why did you leave?

ADRIAN: That's a tough question. I still ask myself that sometimes.

GREGORY: But it was your choice, right? No one made it for you?

ADRIAN: Yes. I was young. And somehow… well, in short, I wanted to come back — so I did. And to be honest, I’ve never really regretted it. Because my career turned out well. I never had to go looking for work elsewhere. I did work again in Poland, in Hungary, and in the Czech Republic. But eventually, I returned.

GREGORY: Let’s move to your work itself. Let me phrase it a bit roughly: do you come up with the story? Or does the screenwriter? Or maybe you adapt literary material?

ADRIAN: I see what you mean.

GREGORY: So how does it work?

ADRIAN: Most often — it’s the screenwriter. I’m not a screenwriter myself. I can take material and work with it — even if it’s just a literary source. For example, when I made the animated film Loskoton, I only had the original text — and that was enough. But writing a script myself… that’s not really my thing. There are animators — quite a few of them — who do everything: write, design, animate. I don’t. I try to do only what I’m relatively good at.

GREGORY: So, what exactly is that? Drawing? Animation?

ADRIAN: No, it’s more about either directing animation — or making an animated film from start to finish. That is: I work as a director, or a producer — and that’s where I feel confident. But to come up with a story or create a vibrant character — that’s not quite my strength. You need to be either a writer or a designer for that. And I’m neither. I’m more the person who brings it all together.

GREGORY: By your age, you must have experienced the Soviet period, right?

ADRIAN: Of course.

GREGORY: And how do you compare that animation — Soviet animation — to what’s being made today? I mean not just in the former USSR, but worldwide.

ADRIAN: Soviet animation mostly came from a few well-known studios. There were the Moscow studios and the Kyiv one. Also in Belarus, and in the Baltics — by the way, they had quite a developed animation scene. There was Pärn, and they made some great stuff — very distinct in style. That’s about it. Maybe a few smaller workshops attached to film studios — but overall, it was just Moscow and Kyiv. There wasn’t much competition per se, but honestly, the Kyiv school was not worse — and in many ways, even better. Freer.

And as for comparing old Soviet animation with—

GREGORY: I mean in terms of quality.

ADRIAN: The West always ran like clockwork. Maybe not everyone agrees with me, but they had a totally different approach. They treated animation like cinema: it was work, it was business, it was big projects. And those projects were interesting — and well made.

Soviet animation worked differently. It didn’t aim to make money — there was a planned economy. A studio had to release ten or twelve films a year. And what we know as "Soviet animation" — that’s just the tip of the iceberg. A huge number of cartoons nobody even saw, because, to be honest, they weren’t watchable.

We all know the Soviet classics — Nu, Pogodi!, Prostokvashino, Winnie-the-Pooh, of course. The old cartoons by Deshkin — Shaybu, shaybu! and so on...

ADRIAN: The Ukrainian studio also made great films. Of course Captain Vrungel, How the Cossacks... — that whole series.

GREGORY: I believe your father had a direct hand in that.

ADRIAN: There was Doctor Aybolit — a blockbuster for all times, Treasure Island, of course. And Alice in Wonderland. A lot of good cartoons. Kotyhoroshko, excellent. Kapitoshka. In short, a ton of worthy works.

GREGORY: And if we compare that... I mean in terms of technology — that animation, or as it was called then, multiplikatsiya. By the way, is there actually any difference?

ADRIAN: None at all. Just in the name.

GREGORY: Just the name? Aha. Because when this English-based word animation appeared, it seemed like it didn’t quite take root in the Soviet Union.

ADRIAN: It didn’t catch on in the Soviet era. But after the collapse — it took root very quickly.

GREGORY: And in essence, what do you think?

ADRIAN: In essence — no difference. You’re still either animating or making cartoons. Doesn’t matter what you call it.

GREGORY: I mean, the word “multiplikatsiya” comes from “multiplication,” right? While “animation” comes from “to animate,” to give life. In that sense, maybe “animation” is closer to the essence of what you do. Or not?

ADRIAN: You know, I’ve never thought about it that way. I don’t care — you can call it a “Christmas tree” for all I care, it still needs to be made and drawn. For me, there’s no difference between “animation” and “мультипликация.” I won’t argue with someone who insists that one is better than the other — to me, they’ve always meant the same thing.

GREGORY: I’ve been thinking about how things were back in Soviet times… I’m talking now about technological progress, which of course affected both the USSR and the West. The West, as usual, was ahead. But back then, if someone from, say, Ulan-Ude wanted to do animation — it was practically impossible, technologically speaking. They had to go to Moscow or Kyiv or some major city. Maybe work as a janitor, marry a local to get residency, enroll in school — and so on. Just to get access to the technology that existed in those big centers. But today — all you need is a computer. How has that changed the landscape of this genre, this field — even this business?

ADRIAN: It hasn’t changed it much, actually.

GREGORY: Why not?

ADRIAN: Because you can sit at home and work on your computer only if you already have a background. If you’re more or less a professional. But if you’re not — if you’re self-taught — then in ninety-nine percent of cases, it just doesn’t work. I don’t mean to offend anyone, but that’s the reality.

GREGORY: But if we compare the quality… let’s say, of the traditional Disney school. Where there were no computers, everything was hand-drawn, right? Artists drawing frame by frame… Now everything’s different. Has this affected the quality of the final product? Or did that old-school style just have its own audience, its own time?

ADRIAN: I get your question. For its time, the technologies they had — that was the ceiling. And for that era, what Disney or European studios were doing — it was all hand-drawn. Pencil on paper, then re-drawn. Then transferred by hand onto celluloid. Then painted — all by hand, hand, hand. Then shot under a camera, with painted backgrounds. It was a long, hard process — but there was no other way. And for that time — it was perfect.

Back then, just like now, there were good cartoons and bad ones. The only thing that’s changed is the tools. It’s just tool replacement, really. Now we have 3D, cut-out animation (which in the Soviet Union was called “перекладка”), animation software — 2D and 3D, tons of options for different tasks. But the idea remains the same. There were good and bad cartoons then — and the same now.

Yes, today it’s hard to find artists who can animate by hand, the way it was done before — that’s a real challenge. But still, it’s possible. Generations have changed, tools have changed. Now they make beautiful cartoons — both in 2D and 3D. Series too. They’re not worse — just different. There’s really no difference in how it’s made. What matters is the story, the idea. Everything else is just a means to tell that story.

GREGORY: I see. So what about the arrival of artificial intelligence in your field — does it bring anything fundamentally new?

ADRIAN: Not yet. Not yet, but it's getting there.

GREGORY: Tell me more. I find this fascinating, because it seems to me that in animation, AI could bring truly revolutionary changes. But I’m no expert.

ADRIAN: Yeah. The rise of artificial intelligence is definitely a major and serious threat to many professions connected with animation and cinema — translators, screenwriters too. There was already a strike — a writers' strike. It was partly about AI. But I still see it as just a tool. That’s all it is. The idea — the script, the concept — that remains unchanged. A good story is a good story. If you can make it with the help of AI, go for it. If not — and for now, that's usually the case — then it won't happen. But for many professions, AI will be a serious headache.

GREGORY: Well, let’s hope that somehow… I mean…

ADRIAN: Look, it’s not the first time this has happened. When 3D came around, all the 2D animators were fainting. Saying things like, “That’s it, it’s over for us,” or “3D will never be as good as 2D, because we draw by hand, with love.” But sadly, that’s just empty talk. 3D didn’t kill 2D completely, but it pushed it aside — took a serious chunk of the industry. And yet, I wouldn’t say it got worse or less soulful. There are wonderful stories. Tons of great, amazing cartoons made in 3D. And today’s kids don’t even notice the difference. If anything, 2D seems a little archaic to them now. But the cartoons are still good. And if in the future they’re made with AI — using artificial intelligence as a tool — why not? It’s just a tool.

GREGORY: Let’s dive a little into your childhood. It was in Kyiv, right? What kind of family did you grow up in?

ADRIAN: I was born and raised in Kyiv. In this strange place called Voskresenka.

GREGORY: Why “strange”?

ADRIAN: Well, it’s kind of a working-class neighborhood full of Khrushchyovkas. Soviet power never really took hold there. It’s a sort of legendary area, in its own way. My parents divorced soon after.

GREGORY: “Soon” — how old were you?

ADRIAN: I was little. I don’t remember much. But both my mom and dad worked at the studio. My sister and I basically grew up there. I knew all the old-timers at the studio since I was a baby. So getting into the profession was… I never really left it, actually. Of course, I did take courses. I drew since I was a kid. Took courses. But for example, my sister didn’t become an animator. She never wanted to. She became a producer. Now the studio we still have in Kyiv is run by her. She manages everything. And I followed this strange road — animation.

GREGORY: Let me quote something you once said.

ADRIAN: Me?

GREGORY: Yes. “The biggest help my parents gave me was not helping much. They threw me into the fire — what I earned was mine.”

ADRIAN: That’s basically how it was, yes.

GREGORY: No hard feelings?

ADRIAN: Toward whom?

GREGORY: Well, I don’t know. Your parents?

ADRIAN: God forbid. Not at all. Quite the opposite — they did watch over me. But I climbed on my own. No resentment. In fact, it was great. Because yeah, on one hand, I did it all myself. There’s no other way. Either you draw and they accept it — or you don’t. Doesn’t matter whose son you are, right?

GREGORY: No daddy’s help here?

ADRIAN: Nope, unfortunately not. Especially abroad — no one knows you. No one cares. You show up, just another worker. You’d better deliver. No one cares who you are, what you were, what your name is. Same goes for here, really. So I made my own way. But to my parents’ credit, they did watch over me. Gave good advice.

GREGORY: Was it helpful?

ADRIAN: Of course.

GREGORY: Life advice or professional?

ADRIAN: Both. They gave advice on life and on the profession. I’ll be honest — I didn’t always listen. In my youth, I should have listened more often. But still.

GREGORY: You made mistakes?

ADRIAN: Who hasn’t?

GREGORY: I mean the kind you could’ve avoided if you had followed your parents’ advice?

ADRIAN: Probably, yes. Of course I made mistakes. If I had listened, maybe I wouldn’t have made some of them. But, you know, even failure is a result. You learn from mistakes.

GREGORY: That’s true.

ADRIAN: Of course, it’s better to learn from others’ mistakes — but your own… they teach you faster. If you’re willing to learn, that is.

GREGORY: At the beginning of today’s talk, you mentioned you’ve never been to Ulan-Ude.

ADRIAN: No, never.

GREGORY: Have you ever felt drawn to Buryatia? Wanted to learn more about it?

ADRIAN: Maybe in the past — just out of curiosity. It’s a beautiful place. But now, I would never go there. We are at war. Buryatia is on Russia’s side. And Russia is our enemy. I won’t go there under any circumstances. Well, unless something drastically changes. Which we all hope for…

GREGORY: Yes. Did you know your grandparents? Did you meet them, know their stories?

ADRIAN: On my father’s or mother’s side?

GREGORY: Doesn’t matter.

ADRIAN: I knew my maternal grandmother well. She raised me.

GREGORY: Was that in Kyiv?

ADRIAN: Yes. She lived in the city center. She would come help us often. Later, she got sick. That’s actually one of the reasons I went to medical college after school. As for the others — I didn’t know them. My mother’s father died in the war. My father’s father was repressed in 1937 and executed. And my paternal grandmother passed away back in the 1950s.

GREGORY: Executed? I thought I read somewhere that he died in prison?

ADRIAN: Either died or was executed — no one knows for sure. In our family archive, we only have one paper: “rehabilitated due to lack of evidence of a crime.” How exactly he died, or under what circumstances — no one knows. Sadly. Not even a photo remains.

GREGORY: Was he the only family member repressed during those years?

ADRIAN: On my father’s side — no, not the only one. His uncle was imprisoned and died there, and there were more relatives. My father’s family was hit hard. On my mother’s side — no one was imprisoned because the war began, and everyone went to the front… and died. My grandfather and his brothers — none of them came back.

To be honest, it hit my father more than me. Because when you’re young — say, twenty — things that happened in 1937 just don’t register. You don’t dwell on it. Now I realize… I’m much older than my grandfather ever was. And my other grandfather — he also died in the war. So, basically, no one came home.

In our family, all the men — all of them — were killed. Only my father lived, thank God, to the age of 90, I hope. But all the others — all the uncles, great-uncles, everyone — over several generations — were killed: in the civil war, World War II, executed, imprisoned — all of it.

GREGORY: If I recall correctly, one of your relatives — maybe even a grandfather — served in Ungern’s army?

ADRIAN: That was my great-uncle. Not my uncle directly — it was my grandfather’s brother. He served in Baron Ungern’s army. He went to Mongolia with the retreating White Guards. He lived there for several years.

Then the Soviet Union said: “Come back, full amnesty, we’ll forget everything.”

And he believed them. Came back. About six months or a year later — they executed him. Just like that. And his whole family too.

GREGORY: That’s not surprising, honestly. Being in Ungern’s army — that kind of mark on your biography couldn’t go unnoticed.

ADRIAN: Of course. That’s exactly my point: you couldn’t trust the Soviets.

GREGORY: That must have been a huge blow for a small republic like Buryatia, right? From what I’ve read — the young cultural and academic life that had just started there took a major hit in the 1930s. Some say it stalled the republic’s development.

ADRIAN: I’d say — it halted development across the entire Soviet Union.

Because… my mother’s from Ukraine, and she’s never been to Buryatia either.

And considering how many people were imprisoned, then how many died in the war — of course that had to stop a lot of social and cultural processes. But… that’s just how it turned out.

GREGORY: What do your Buryat roots mean to you personally?

ADRIAN: Well, the roots are there — but I grew up in Ukraine. And honestly, other than the fact that I’m half Buryat, I have no real connection to Buryatia.

I was born and raised in Ukraine, went to school there, graduated from college, worked — all my friends, my whole family — they’re all in Ukraine.

GREGORY: Do you speak Ukrainian?

ADRIAN: Of course. And I write in it too.

GREGORY: Since school?

ADRIAN: Yes, since school. Though, during Soviet times, learning Ukrainian in Kyiv wasn’t easy. But I was lucky — I went to a Ukrainian-language school. Most schools were Russian-language, and Ukrainian was taught like a foreign language — once a week.

But I went to a Ukrainian school, so I speak well, write without mistakes, and read fluently. It’s like my second mother tongue — actually, like my first. I never really made a distinction between the two. Ukrainian or Russian — it makes no difference to me.

GREGORY: How do you see the place of Ukrainian culture in the global context?

ADRIAN: I see it positively. It could be more prominent, of course, but luckily the world is learning more and more about Ukraine. In Canada, Ukrainian culture has always been well represented. There’s a big diaspora here, and they value and remember their roots. I’ve met people here who were born in Canada — grown-ups — who still speak Ukrainian. They remember where they come from. And that’s wonderful. I hope Ukrainian culture will continue to develop and spread.

GREGORY: You know, while preparing for our meeting, I read your father’s memoir. I understand he could have written a lot more, but the piece is called Remembering Ulan-Ude. There’s a passage about his entrance into VGIK. He mentions some amazing names — people who are now well known among those interested in cinema. And then suddenly there’s this phrase: “I felt a sense of inferiority.” That stopped me. I thought — of course, it’s natural — a man from a small northern town arrives in the capital. Even if Tarkovsky wasn’t yet Tarkovsky, the feeling is understandable. But then he writes: “It was because I didn’t speak Buryat.” That struck me deeply.

ADRIAN: Yes, my father didn’t really speak it, because by that time the Buryat language had been almost completely displaced. And now, as far as I know, very few people speak it. The Soviet Union did everything it could to suppress national identity. That’s how it seems to me. Ukraine is a good example — I remember from my childhood: in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odessa, Eastern Ukraine — one Ukrainian school per district, at best. Yes, newspapers and signs were in Ukrainian, but everyone spoke Russian — the vast majority. It was considered normal. And only after the collapse of the USSR did Ukrainian start to revive. But in Kyiv, there was never a real problem with bilingualism. Some spoke Ukrainian, some didn’t — it was never an issue until people started “defending” the Russian language. That was a strange claim. I speak Russian well, and growing up in Kyiv, no one ever made a problem out of it. I could switch to Ukrainian, but mostly we spoke Russian.

GREGORY: Yes, that’s understandable.

ADRIAN: And I think that’s how it was with the Buryat language. My father speaks it poorly… well, he knows some basics, but his family didn’t use it. His mother was a Russian language teacher.

And his father — my grandfather — was imprisoned.

GREGORY: Was he the one who served as the first Minister of Health of Buryatia?

ADRIAN: Yes… He was also a venereologist, which saved him.

GREGORY: How so?

ADRIAN: He was the only one who could treat the big shots for their “fun” diseases.

GREGORY: I suppose that was postwar?

ADRIAN: Pre-war, actually.

GREGORY: Oh, I thought it was after the war.

ADRIAN: No, I think it was before.

GREGORY: Did you know your grandmother on that side?

ADRIAN: No, she died long before I was born. But she almost got arrested too — fortunately, the war started. So they forgot about her.

Otherwise, my father grew up as the son of an “enemy of the people” — which meant poverty, misery, utter hopelessness.

Only after his father — my grandfather — was rehabilitated was he able to go to university. Otherwise, I don’t even know what he would’ve done.

GREGORY: I read another phrase: “I became Ukrainian thanks to Soviet power.” He meant…?

ADRIAN: He was assigned to Ukraine — yes, exactly.

GREGORY: After graduating from VGIK?

ADRIAN: Yes, after VGIK he was sent to Kyiv. He started at the Dovzhenko studio, worked there with Ukrainian directors for a while.

Then he moved to the newly established Kyivnaukfilm animation unit — where he spent his whole life.

GREGORY: Where were you when the war began?

ADRIAN: When the war started, I was in Armenia.

GREGORY: Armenia?

ADRIAN: Yes.

GREGORY: Were you living or working there?

ADRIAN: I was living there. I left Ukraine in 2014. I started another studio in Armenia. I lived and worked there. When the war began, I was in Yerevan. My wife woke me up and said Kyiv was being bombed. At first, I simply didn’t believe it —

even though everything had been pointing to it.

GREGORY: So you had a feeling that war was coming?

ADRIAN: I didn’t believe it, but the facts pointed that way.

GREGORY: There’s another topic related to the war that I can’t ignore... It so happened that Buryats gained a particularly negative reputation in this war. As people directly involved in war crimes — let’s be honest. How did that happen? Why the Buryats?

ADRIAN: I don’t know. I can’t answer that. I can only guess — and those guesses are baseless.

GREGORY: Well, your guesses?

ADRIAN: It’s not just about the Buryats. They’re just part of it. It’s more about despair. They’ve been pushed into such conditions... The whole Russian system. That’s the hinterland. There, it’s either drink yourself to death — or this, at least you get to see the world. These are people cornered into such conditions that they become savage. It’s not just the Buryats. It’s the entire Russian hinterland — cheerfully running off to earn money. It’s the same thing. That’s how I see it. And the fact that the Buryats stood out so much in this war... It’s painful and shameful to me, to some extent. But… these are facts. And what can I do about it?

GREGORY: In your opinion, on a basic human level — Ukrainians and Russians... when might they be able to live together again? I won’t say “friends,” but at least live, talk?

ADRIAN: I think several generations will need to pass. If we look at the postwar experience — like Germany — it took generations before people could view Germans without hostility. For example, my mother lost her father in the war — and to this day, she can’t bear the German language. She just can’t help it. It’s in her — from birth, from upbringing. So yes, several generations must pass before anything can get better. But first, something must happen inside Russia. Because right now — reconciliation is impossible.

GREGORY: Even if Putin is gone?

ADRIAN: Even if Putin is gone. They’ve sown so much evil, so much grief, so much hatred. And the worst part — no one forced them. They opened Pandora’s box themselves. And I hope they pay for it. I once heard Parfyonov say: “When the war ends, the worst will be behind Ukraine. But for Russia, the worst will still be ahead.” That’s what we’re all hoping for.

GREGORY: How did you end up in Canada?

ADRIAN: Through the CUAET program for Ukrainians. When the war began, I was living in Armenia. On February 25 — the day after the invasion — my wife, my eldest son, and I went to the Russian embassy with protest signs. We were out there for five minutes before the Armenian police showed up and politely told us to leave. “We understand,” they said, “but just wait a week — this will all be over.” That moment made me feel something was very wrong.

GREGORY: So you didn’t feel safe there anymore?

ADRIAN: No. A wave of Russians started flooding into Armenia. Flights were packed. You’d hear Russian everywhere — more than ever before. Tensions began to rise in public spaces. And although Armenians are a kind and generous people, I felt like I no longer belonged. We kept attending protests organized by the Ukrainian embassy. Some Russians and Belarusians joined too — which was unexpected. But emotionally, I couldn’t stand being surrounded by Russians anymore. Even though I had many Russian friends — especially from my time working in Hungary — after February 24, it all just… cut off.

GREGORY: So what did you do?

ADRIAN: We packed our whole life into four suitcases. I applied for a Canadian visa through CUAET but didn’t leave right away. First, I tried to get my parents out of Ukraine — but they refused. My father said, “This is where I live. This is where I’ll die.” Even after an explosion shattered their windows, they wouldn’t budge. My sister, who was taking care of them, couldn’t convince them either. So we went to Europe. First — a refugee camp in Germany. Then — Belgium, where I found work. After my contract ended, we moved to Canada. It made sense: English-speaking, with a large animation industry.

GREGORY: You have a reputation for being resourceful and entrepreneurial. How has your integration into Canadian life gone?

ADRIAN: Integration is still ongoing. I wouldn’t say I’ve fully landed. Yes, I used to be seen that way — but here I haven’t found steady work in my field. It’s hard. There’s intense competition and very few jobs. Studios are barely surviving — they don’t have room for newcomers, especially someone “old,” without Canadian experience, with imperfect English. Even though no one actually tested my English. I get it — they want to play it safe. There just aren’t enough projects to go around. A hundred locals apply for every position. It was a huge blow — animation is the only thing I’ve ever done.

GREGORY: And yet — here you are.

ADRIAN: Yes, I’m standing. I had to reinvent myself. I retrained and started working with AI tools. If you can call that work. But at least now, it pays the bills.

GREGORY: Could you tell us a bit more about how this works?

ADRIAN: Sure. About a year ago, just out of boredom, I started reading, researching, and making some first attempts—just for myself.

Since I’ve spent my whole life making cartoons and commercials—I really enjoy this kind of work—it’s very discipline-focused.

And when it comes to reputation, it's mostly because I worked in advertising. And advertising is all about discipline.

Actually, it was my experience at foreign studios that taught me discipline.

We had a great studio in Kyiv, but we were far from having proper work discipline for many reasons.

On the contrary, I always tried to make sure everything was structured properly.

I made one commercial, then another, then a third, and I started digging into all these tools. Now, thanks to that, I’m staying afloat.

In fact, I’m even thinking about opening something similar here, because I don’t see many such specialists in Canada.

So that’s how it is. I make videos, ads, commissioned work. Someone even ordered the first chapter of the New Testament—I made it.

And surprisingly—it shocked me too—it turned out really well.

So, yeah. It’s a dangerous tool. A very dangerous one.

GREGORY: What do you see as the danger, apart from some specialists potentially losing their jobs?

ADRIAN: Well, that’s a serious issue. Of course they'll be lost. They'll be out because—when it comes to choosing between money and a specialist—a producer will pick the money. No question about it. Why keep, say, a whole team of professionals: cameramen, sound engineers, voice artists—when we’re talking about film and TV jobs—if one person can now do it all in a couple of hours? I’m exaggerating, but still—it’s a major threat. And the second big threat is that it dumbs people down. Because everything becomes too easy.

GREGORY: So this dulls both the creator and the consumer?

ADRIAN: Both. It’s pretty hard to become a professional in this field now. I mean, it’s possible, but it’s hard.

What does it even mean to be a professional? It just means you write better prompts than others.

For me, my qualifications help — I know how to assign tasks to performers, like animators.

I can make a storyboard, break down shots for editing, and tell a story.

But most people don’t care about that. They just go: “Whatever I want, I’ll do.”

And they do. It dulls both the performers and the audience.

What’s more, good luck getting someone to watch something longer than three minutes now.

Three minutes is the maximum you can hold a general viewer’s attention.

Everyone’s been ruined by TikTok, YouTube Shorts, and Facebook Reels.

Three minutes — and that’s it.

And AI makes stunning, beautiful things for this — mostly meaningless, but still.

I’m talking about video generation here.

And school kids — why read a book anymore?

“What’s the book about? Let me tell you in two sentences.” That’s it. That’s enough.

And I think it’s really going to hurt the quality of education and ingenuity.

Because a teenager without the internet is like a fish out of water.

Even I notice it in myself — if I forget my phone, I’m like: “What do I do now? How do I look anything up?”

That, I think, is the problem.

GREGORY: Alright. So to sum up, would you say you’ve found yourself in Canada?

ADRIAN: Not yet. I’m still in the process.

GREGORY: Then all I can do is wish that your search doesn’t take too long — and that you show your best professional and human qualities in this country. I hope everything turns out well for you.

ADRIAN: Thank you very much. Let’s hope so.

GREGORY: Just a reminder — our guest today was director Adrian Sakhaltuev.

Thank you for watching. Take care, and see you next Saturday.