Lidiya BOYKO

Born on February 10, 1946, in the village of Trypillia near Kyiv.

Lidiya’s childhood took place in the difficult post-war years. Her parents lived and worked in Kyiv, where food and housing were scarce. Until the third grade, she was raised by her grandmother near Chernihiv—this period remained the brightest memory of her childhood. Later, she returned to Kyiv, where she completed her schooling.

From an early age, she was passionate about mathematics and physics, dreaming of becoming an astronomer or nuclear physicist. She also loved music, learned to play the bayan, and actively participated in school performances.

After high school, she enrolled in the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics at Kyiv State University, but after a year, she realized that her true calling was the stage. She passed the entrance exams and was accepted into the Kyiv National University of Theatre, Cinema, and Television named after I.K. Karpenko-Kary, graduating in 1969.

After completing her studies, she was assigned to the Russian Drama Theater in Dnipro. She later worked at the Novokuznetsk, Tula, and Stavropol theaters.

In 1976, she was invited to Moscow to join the Taganka Theatre. Working with outstanding directors such as Yuri Lyubimov and Anatoly Efros became a unique school of acting for her. It was there that she fully understood the meaning of the famous phrase: «Love the art in yourself, not yourself in the art.»

In 1990, she emigrated to Canada and settled in Toronto. She became part of the Russian-speaking theater community and collaborated with Olga Shvedova’s theater studio. Over the years, she played numerous roles in both classical and contemporary plays and appeared in several films.

GREGORY: Hello, dear viewers, this is the program Interview Hour, and I am Gregory Antimony. It is my great pleasure to introduce my guest today — actress Lidiya Boyko. Thank you for coming and accepting our invitation. I know you recently had a birthday. How did you celebrate it?

LIDIYA: At home with my husband.

GREGORY: As usual?

LIDIYA: As usual, nothing special.

GREGORY: What was it like in your childhood?

LIDIYA: I don’t remember.

GREGORY: Come on.

LIDIYA: Well, you know how it is in childhood… A post-war child. First of all, I was raised by my grandmother in a village.

GREGORY: Where was that?

LIDIYA: It was in Ukraine. A village near Chernihiv. My parents were in Kyiv, but I lived with my grandmother in the village. There was nothing particularly special. I don’t even remember my birthdays when I was little. I just don’t remember them.

GREGORY: Why weren’t you with your parents?

LIDIYA: My parents were earning money; they worked and rented a tiny, tiny room somewhere on Podil, in some house. It was just like a closet, very small, there was simply no space... And only when I was in the third grade did they take me away from my grandmother. But I remember my life with her very well — it was wonderful, though very difficult. And then, after third grade… Honestly, I don’t remember my birthdays at all, not a single one from my childhood. Life was very hard.

GREGORY: And you don’t remember any gifts either?

LIDIYA: Gifts? No gifts. I do have some vase left—I remember in the fourth grade, the other kids gave me this vase.

GREGORY: My childhood also wasn’t easy, though I didn’t grow up in a village. Although, for a period, my parents—who were doctors—traveled between small towns and villages in Ukraine after finishing medical school. I was their only child, so I have some memories from that time, though, I must admit, aside from one occasion, I don’t remember my birthdays either. What I do remember is that we were often quite hungry. That, I recall very well.

LIDIYA: What I remember most from my childhood is how my grandmother took me to church on Easter morning. It was early, freezing cold, and there was no church. The church near our home had been turned into an electric station and a bathhouse. That I remember very clearly.

GREGORY: A bathhouse?

LIDIYA: Yes, a bathhouse and an electric station were housed inside the church building. Naturally, religious people never went to that bathhouse. And I remember how my grandmother took me to Easter service in the freezing cold. She wrapped me in a scarf and dragged me along. There was a large wooden house, a crowd of people, it was unbearably hot inside, the air was thick, and candles were burning everywhere. That is one of my strongest childhood memories. My grandmother didn’t live with my grandfather. And once, he gave me three rubles as a gift. I tell this just to show how difficult life was back then. So, I took those three rubles and went to the store to buy myself a tiny toy primus stove. My grandmother didn’t speak to me for a whole week because I had spent that money on a toy. My grandmother worked in a collective farm. And I remember that I had to pick grass to feed the cow in the evening when she returned…

GREGORY: Your grandmother had a cow?

LIDIYA: My grandmother had a cow and a pig, but that didn’t mean we lived in abundance. On the contrary, life was very hard. Every day, I had to gather two baskets of grass to feed the cow when she returned from the pasture. Of course, I would gather just a little, then fluff it up to make it look like more… These are my childhood memories.

GREGORY: What language did your grandmother speak?

LIDIYA: She spoke Ukrainian. But when she came to Kyiv, she could switch to Russian. My parents also spoke both languages—sometimes Ukrainian, sometimes Russian.

GREGORY: And you speak Ukrainian?

LIDIYA: Yes, I can, I do. Moreover, I graduated from the Karpenko-Karyi Theatrical Institute, where the education was in Ukrainian. But after graduation, I immediately left to work in a Russian theater in Dnipro. I spent my first year there, then moved to Novokuznetsk.

GREGORY: Well, we’ll get back to that. Was the school in your village a good one?

LIDIYA: Yes, I suppose so, just an ordinary school.

GREGORY: You don’t remember it well either?

LIDIYA: I do remember one thing—how they made me a snowflake costume for New Year’s. My grandmother sewed it from gauze, with a kind of gauze veil on top.

GREGORY: So you were a snowflake.

LIDIYA: Yes, some kind of snowflake. I also remember that when I was in first or second grade, they invited me to play Ded Moroz (Father Frost) in a kindergarten. Apparently, I had a loud voice. I would recite: Not the wind that rages over the forest...

GREGORY: You never played Snegurochka?

LIDIYA: No.

GREGORY: By third grade, you moved to Kyiv to live with your parents. Do you remember that well?

LIDIYA: Yes, very well.

GREGORY: What was your family like?

LIDIYA: My mother was an accountant, and my father was a geologist. For a while, he didn’t live with us, but then he returned. I had some lung issues back then—doctors found a shadow on my lungs, and at that time, there was a crackdown on doctors. Everyone was saying: "It’s the doctors’ fault, they ruined the child’s health."

GREGORY: You were five years old?

LIDIYA: Yes. They sent me to a sanatorium, and that’s where I saw my father for the first time after a long separation. They told me, "Your father has come to see you." And there he was, stepping out from behind the building… Then life became more normal—poor, but stable. We lived like that until the eighth grade, then we got an apartment, moved to Chokolivka, and I continued my studies.

GREGORY: What did you do besides studying?

LIDIYA: Gymnastics. I was a master of sports in rhythmic gymnastics.

GREGORY: I thought it was artistic gymnastics.

LIDIYA: No, rhythmic gymnastics. I wasn’t accepted into artistic gymnastics because my body structure didn’t fit. But I’m very glad I did rhythmic gymnastics. In school, my favorite subject was physics. In fact, I wanted to become a nuclear physicist… No, actually, I wanted to be an astronomer or work in nuclear physics. That’s why I was good at math. After school, I entered Kyiv University to study physics and mathematics and completed my first year. Do you remember that old Kyiv University building? I don’t recall the street, but the building was red. It was painted red because executions had taken place there… I’m not sure of the exact history, so I won’t claim it as fact. The walls were incredibly thick! When you walked in, it felt like stepping into a crypt. That oppressive red color… It affected me so much that I decided I wouldn’t be a physicist—I would become an actress instead.

GREGORY: Did you have a good relationship with your parents?

LIDIYA: Yes, it was good, but I wouldn’t describe it as warm or friendly, as many do. My parents were focused on making money to feed the family and survive in that difficult time. Later, my mother spent two years in prison. She worked as an accountant in a village, I think in Trypillia. The head accountant framed her for something, and she was imprisoned. After that, my aunts, my mother’s sisters, took me in. By that time, I was already living in Kyiv. My father wasn’t around during that period. I was still very young. Honestly, I don’t have a clear timeline of my life. I don’t keep track of chronology well—I just remember moments.

GREGORY: Do you remember the moment when your mother returned from prison?

LIDIYA: No. I don’t remember. She came back, and life went on. I don’t even know if I was with my grandmother at the time or already in Kyiv—probably with my aunts.

GREGORY: If someone asked you today whether your childhood was happy, what would you say?

LIDIYA: Childhood… It always seems happy when you look back on it. But if I’m honest, analyzing my career and understanding my abilities, I realize that I couldn’t achieve more because of my childhood. I grew up with terrible insecurities. For example, when my school had outings, all the children dressed nicely, but I always wore something very modest and poor. That probably shaped my character—to stay on the sidelines, not stand out, to be like a little mouse. But at the same time, I always felt that there was something inside me. That’s why I became an actress.

GREGORY: Acting requires you to show yourself, to be brighter than others. It’s always a competition.

LIDIYA: Yes. But you know, the hardest state to be in on stage is when you walk out and realize you can do anything. You are the best, you can do it. But the moment a thought creeps into your mind—what if someone else is better? What if I fail? What if something goes wrong?—it’s over. That’s it. It was the same for me in gymnastics. Why did Olya help me so much? Because she believed in me. She gave me roles that helped me feel completely free on stage. In the last play, “Harold and Maude,” I felt like I could do anything on stage, whatever Olya asked of me.

LIDIYA: Unfortunately, I didn’t carry this over from childhood. I always had a block, a constant fear that I was doing something wrong.

GREGORY: Did you go straight to theater school?

LIDIYA: Theater school? Well, I was at university first, then I transferred to the institute based on my university transcript because my documents were already there…

GREGORY: Right, but you still had to perform something for your audition?

LIDIYA: Yes, of course. We had a theater club in school, like always. I remember we performed Komsomolsk-on-Amur, or maybe the play had a different name.

GREGORY: City at Dawn.

LIDIYA: City at Dawn, that’s right. I played a role in it. The club was led by a woman whose husband was a professor at the Kyiv Theater Institute. I guess she liked what I was doing, so she told him about me.

When I auditioned, he was on the selection committee. He was a real master, and he told the professors taking students for the first year: If you don’t take her, I’ll take her on my second-year course.

So, of course, there were three audition rounds, as in any institute. A lot of people competing for each spot. But I got in fairly easily, and honestly, those were some of the best years of my life.

GREGORY: Your studies?

LIDIYA: I have great memories of my time at the institute. I remember we used to go caroling on Christmas. It’s funny, I don’t recall events in chronological order, but I remember the brightest moments.

We would dress up in costumes, grab our bags, and go house to house singing Shchedryk, shchedryk, shchedrivochka… We went to the Writers’ House, and a writer came out and said: Oh, thank you! Here’s my book as a gift. And he put it in our bag.

We were thinking: A book? We’re hungry students, and he gave us a book!

Then we went to one of our classmates’ parents in Darnytsia, and that was truly wonderful. They welcomed us warmly, treated us to food. Those are the kind of memories that stay with you.

GREGORY: Human memory doesn’t store things chronologically. It just brings back moments that suddenly light up. Okay, so you finished the institute—where did you go next?

LIDIYA: To the Dnipro Russian Theater.

GREGORY: Did they invite you?

LIDIYA: No, we went there ourselves to audition. We performed the final scene from Masquerade by Lermontov. I played Nina. The director accepted us.

That summer, we went to the acting job market in Moscow—back then, there was an official casting exchange for actors. There, we met Valya Tkach, a graduate from the Leningrad Institute. He had just been appointed as the chief director of the Novokuznetsk Theater and was forming a troupe of young actors. He recruited me and convinced me to go.

I ended up going God knows where, leaving Ukraine for distant Novokuznetsk. And there, he had another director, Yura Pogrebnichko. Do you know him?

GREGORY: Yes, very well.

LIDIYA: That was my golden time in Novokuznetsk. Valya staged "The Robbers", and I played the lead. Then Yura staged "The Three Musketeers", where I played Milady, and "The Golden Coach".

But within six months, the press was no longer allowed to cover the theater for some reason. And then, another six or seven months later, the company was shut down. The theater itself remained, but our group was dissolved.

GREGORY: Why?

LIDIYA: It was a very modern theater, with remarkable performances. But it wasn’t the usual old-fashioned type of theater—it was something fresh, with young actors. And that’s often seen as a threat.

GREGORY: I don’t quite understand—who would have had a problem with that?

LIDIYA: I don’t know.

GREGORY: What year was this?

LIDIYA: 1969, 1970.

GREGORY: Someone didn't like it.

LIDIYA: Then they appointed different people. Yura and Valya were either fired or left on their own. Radul became the chief director—perhaps you’ve met him—and Borat was appointed as the theater’s director. At the end of the season, I left—first to Tula, then to Stavropol. Essentially, I followed Valentin because I saw him as my director; by then, he was already in Stavropol. Then, when we were on tour in Vladimir, Glagolev, Lyubimov’s assistant, arrived. He saw me in a performance, as well as another actor, Misha Lebedev.

GREGORY: Boris noticed you.

LIDIYA: Yes. He invited us to audition for Lyubimov. That was in 1975, and by January 1976, we had already moved from Stavropol.

GREGORY: You traveled quite a bit.

LIDIYA: Yes.

GREGORY: Which play did you have the lead role in?

LIDIYA: "The Star and Death of Joaquin Murieta". That was directed by Tkach, right after the murder of Allende. He staged it before Zakharov did.

Valya structured the entire production as if it were taking place in a stadium—one where people had once been herded in. The whole play unfolded in that setting, and you can imagine the state the audience was in. When, for example, Ohara’s hands were cut off—it wasn’t staged like a musical, but on a whole different level…

GREGORY: So there were no elements of a musical?

LIDIYA: No, nothing like that. It was a powerful, poetically charged performance, but not a musical at all. The music was used as a background, and if there were any songs, they were more like dramatic inserts rather than traditional musical numbers.

GREGORY: Alright, so Boris Glagolin, the second director of the Taganka Theatre, noticed you. What happened next?

LIDIYA: Then Misha and I arrived at Taganka. I really wanted to be there… Back in university, I had read excerpts from Antiworlds, and I absolutely loved it. The directors at our theatre were also trying to stage something similar. I don't even remember if I read it in Ukrainian or Russian… I think it was in Russian. I recall the line: "Their Majesty wants some entertainment; the crowd rushes in from Kolomna."

GREGORY: Did you like Voskresensky?

LIDIYA: Yes, I did, though not everything. But I was particularly fascinated by everything related to Lyubimov’s theatre. I believe we had the full script of Antiworlds.

GREGORY: By that time, what did you know about Lyubimov’s Theatre? You must have heard of it.

LIDIYA: When I was in Novokuznetsk, I was awarded a trip to Moscow as the best actress. Volodya Lychagin was there too—he later stayed in Stavropol. While in Moscow, we went to the theatre and saw Wooden Horses. I remember our director, Valentin Tkach, saying that he had seen the play and compared Alla Demidova’s acting to that of Spencer Tracy—her performance was just that outstanding.

GREGORY: I think Wooden Horses premiered in 1974.

LIDIYA: I don’t remember exactly. Maybe I saw it in Tula, maybe in Stavropol… But I definitely associate Novokuznetsk with that play. Before I got to Taganka, I had already seen Wooden Horses and Comrade, Believe. Comrade, Believe—now that was a masterpiece.

GREGORY: That’s my favorite play as well.

LIDIYA: Mine too. When Vanka Dykhovichny walked between the rows…

GREGORY: And stepped on everyone’s feet…

LIDIYA: It was amazing! All the performances were incredible. And the staging of the carriage… David Borovsky's design was something fantastic. That production shook me to the core.

GREGORY: Well, you ended up in this legendary theater, the one that not only all of Moscow but the intellectual world of that time, including foreigners, was drawn to. Vysotsky, Filatov, Zolotukhin, Demidova—all were there. How did you feel?

LIDIYA: Restrained, tense. I never felt inferior just because I was next to Vysotsky or Demidova. If I felt insecure, it was only on stage—fear of doing something wrong, fear of rehearsals. In life, I never had that kind of reverence for authority. I respected them, observed them, evaluated their talent—where they were stronger, where they were weaker. But I never had that sense of idolizing actors. But with Lyubimov… I think everyone was afraid of him. And it wasn’t fear in the usual sense—it was something else.

GREGORY: How did that manifest?

LIDIYA: I played in the performance Crossroads, based on Bykov’s work.

GREGORY: Not a great production, by the way.

LIDIYA: I only performed in it once. It had a very intense monologue and a complex set—it was scary just moving around without falling. After the performance, I approached Lyubimov, and he said, "Never act at the absolute limit, don’t push yourself to the ceiling."

GREGORY: At the breaking point?

LIDIYA: Yes. He meant that you should always leave some reserve. And then he added, "We’ll rehearse." But what I remember most is his gaze. If he wasn’t interested in an actor, he would look at them with a dead, icy blue stare. It was a terrible feeling—you felt like you ceased to exist for him.

GREGORY: And you felt that towards yourself?

LIDIYA: In the theater, I had my place, my niche, but I was never among his favorites. I was there because I pushed forward myself, tried things, sought out roles. That changed—but too late. In 1990, before we left, there was a Kapustnik (a kind of theater cabaret performance). Venya Smekhov and Nikolai organized it, and Lyubimov unexpectedly got involved and started attending rehearsals.

GREGORY: That was after Lyubimov returned?

LIDIYA: Yes. We were already set to leave for Canada, but we were still going through Austria first. And after the Kapustnik, he suddenly told me, "Rehearse whatever you want." I replied, "Thank you." But I already knew I was leaving, though I hadn’t told him yet. Then I saw the official order—I had been assigned the role of Raskolnikov’s mother, the one Demidova played. So I approached him and said, "I’m leaving. Do you think I should start rehearsing?" He said, "No, there’s no point. You’re making the right decision. Nothing good is going to happen here."

GREGORY: And you were okay with that?

LIDIYA: Yes. I enjoyed being in the theater, doing what I was doing, trying to embody his vision. But I never aimed for major roles. Honestly, I didn’t even want them—it was too much responsibility. Since childhood, I was never used to doing something grand.

GREGORY: How was the rehearsal process with Yuri Petrovich different from working with other directors?

LIDIYA: First and foremost, he knew exactly what he wanted. He had a clear vision of the form of the play, the scenes, and that was what attracted me. I didn’t need to be pushed in any direction—I had to fill the role myself. He guided the actor, but only within the framework that he needed, without allowing them to wander off into unnecessary details. His precision and confidence in his work were astonishing. That’s why his theater lived on and continues to exist—he knew exactly where to place the actor, and how they would fill the role was up to them. The main thing was not to get lost.

When I arrived, there was an exchange rehearsal going on, and I was immediately given the role that Vika Radunskaya had played. I was alone, I knew no one in Moscow, and then came the first rehearsal... I stepped onto the stage, and I had the same overwhelming feeling as when I saw my father again after a long separation.

On that wave of intensity, I played the scene, and rehearsals had only just begun. Velikin came up to me, someone else did too, and they said: “Now he’s going to mold you.” And I didn’t even know what that meant back then. When an actor did something right, he latched onto them and started refining and refining… but in doing so, he could end up stifling the actor. You have to let them go once they understand what’s needed. But no, he kept working, because he saw the result.

At the next rehearsal, I came out, and the feeling was gone. And I have this nature where I can’t repeat myself—if I played the scene one way at one rehearsal, at the next, I needed to find something new. But that’s a lack of proper training. If you don’t have the technique to solidify your results, you won’t become a truly great actor. And that was it—I started doing things wrong. And he immediately said: “Vika, get on stage.” And after that, things changed…

GREGORY: Why do you think Lyubimov’s productions had such an incredibly long life?

LIDIYA: Because they had a powerful form. Each actor could fill it with their own substance. Form is the foundation. Without it, a play falls apart. Of course, it evolves over time, but it only truly collapses when the actors are no longer able to give it the depth it needs.

Yuri Petrovich was incredibly talented. I don’t like to throw around the word “genius”, but he was a truly great director.

GREGORY: I’d argue with that.

LIDIYA: That’s impossible to dispute…

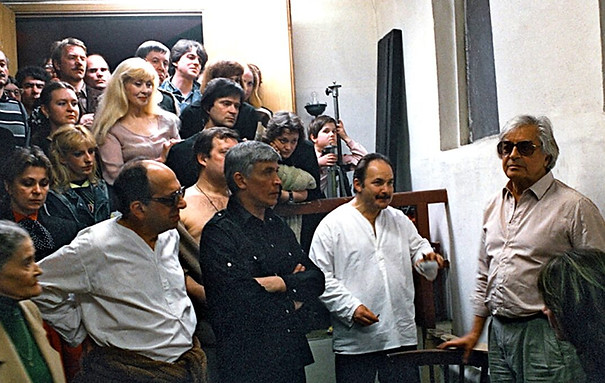

GREGORY: There were three equally significant figures in that theater: Yuri Petrovich, David Borovsky, and Vysotsky. They each contributed in different ways... But another crucial factor was the intellectual atmosphere. Unlike other theaters, Taganka was surrounded by a powerful cultural and intellectual circle. Writers, poets, scientists, the greatest minds of the country gathered there. Did you feel that?

LIDIYA: Absolutely! There was this deep sense of belonging, even if you weren’t officially part of the artistic council. You saw these people, you could talk to them… and it was incredible. I don’t even know how to describe it. Maybe pride? That you were there, among them…

But as I’ve said before, I don’t idolize authority figures.

GREGORY: Do you remember the discussions after the “Vladimir Vysotsky” play when it was banned?

LIDIYA: Yes, I even have a full transcript of those discussions.

GREGORY: Did you personally feel that the theater might be shut down?

LIDIYA: Everyone around was convinced that it wouldn’t happen, so I never had the feeling that the theater could be shut down. Not at all. People who communicated with Petrovich and others—some knew something, some guessed—but they all said, “No, it won’t happen.” I don’t know what they were basing it on, maybe it was just their inner conviction. Just like when they said, “Yuri Petrovich will come back.” On what grounds? What were the prerequisites? But they were sure. I never felt that the theater could be closed, not for a second.

GREGORY: And those years without him?..

LIDIYA: I never understood the attitude of the guys toward Efros. Not at all. I deeply respected Efros as a director. He wasn’t my director, I wasn’t his actress, but I respected him. And yet, the way they treated him... Venya Smekhov, Lenya… they left the theater. They believed that…

GREGORY: But they all left for different reasons, let’s put it that way.

LIDIYA: Yes, during Efros’ time. And now, when I read comments saying, “the entire troupe rejected him”—that’s not true. Only part of them did.

GREGORY: “The entire troupe” meaning what?

LIDIYA: That everyone opposed him, that they treated him terribly…

GREGORY: I think that’s a lie.

LIDIYA: Some conflicts, intrigues… I never saw anything like that. A few people left—that was their right. They didn’t want to work with that director.

GREGORY: The first to leave was David Borovsky.

LIDIYA: Yes. But when people say that the entire troupe rejected Efros—that’s simply not true.

GREGORY: What was your impression of Vysotsky?

LIDIYA: My husband once came to the theater and heard Vysotsky talking somewhere behind him. He said, “I turned around, and it wasn’t what I expected…” When I joined the theater, many people told me what he used to be like—more open, more friendly. That he could just come up and say, “Oh, come listen to my new song…” But by the time I arrived, that wasn’t happening anymore. He would come in, and you could feel that everyone around him tensed up a little, as if gathering their thoughts. Because he took rehearsals very seriously, and he took everything he did very seriously. Everyone felt it. So for me, it was simply: “Hello” and “Goodbye.” We never had any personal conversations.

GREGORY: Who did you become close with during your time at Taganka?

LIDIYA: My close friends were the girls from our dressing room—Lida Savchenko, Lёnya’s first wife, Lena Kornilova, and Lena Gabets. We all got along well, and I had a particularly wonderful relationship with Tanya Zhukova. By the way, Masha Politseymako and I share the same birthday. We were very close; our dressing room was a special place where everyone supported each other. But if we talk about my closest friends now, they are Lena Gabets and Tanya Ivanenko. We still call each other and exchange holiday greetings. Of course, it's been 30 years since I left, and now everyone has their own life.

GREGORY: So, if we sum up your Taganka journey, how would you evaluate it? You joined such a legendary theater, but in the end, you didn’t leave a significant mark there, did you?

LIDIYA: That’s true. But the theater left a significant mark on my life.

GREGORY: That’s exactly what I wanted to say.

LIDIYA: It was my school. A real school. If I had come to another theater first with this kind of training and only then to Taganka, my life would have turned out very differently. I really enjoyed it… Do you remember how Dima and I climbed during "Vysotsky"? At first, Lyubimov included this moment in the performance, then he removed it. We sang: “If a friend turned out to be…” And then: “Are you traveling by train, by car…” It was wonderful. Since this interview is about me, I’ll say this: I started off quite timidly, but then… Lida Savchenko once told me that Lenya came back from rehearsal and said, "She’s getting better and better!" And with Nina, we sang "Truth and Lies."

GREGORY: But that song was later cut from the performance.

LIDIYA: It was in the premiere, but then it was removed. And rightly so, because the play was too long, and it needed to be trimmed down to keep only the most important parts.

GREGORY: The Taganka Theater is probably the most important chapter in your life.

LIDIYA: Yes. Yura Pogrebnichko staged "Province", based on Vampilov. Or rather, he rehearsed it and presented it to Yuri Petrovich. I played the neighbor in that production. And after that performance, Yuri Petrovich told Galina Nikolaevna, who was the troupe manager: "I was wrong to keep her in the shadows all these years." But the play was never staged. No one really liked it. Yura had a very specific directorial vision, completely different from Lyubimov’s. He was closer to Efros in style. But even with Efros, he had his own unique approach. He now has his own theater in Moscow.

GREGORY: Pogrebnichko? Yes, I know. Yuri Petrovich always noticed interesting people, even if they followed their own path. None of them worked in his style, but he supported them. Anatoly Vasilyev, for example...

LIDIYA: We rehearsed with Vasilyev. But nothing ever came of it. We worked on "Claude", if I remember correctly, and "The Bathhouse". But it all remained at the rehearsal stage and never made it to the stage.

But regardless of everything, the theater played a huge role in my life. In 1980, or rather in 1979, when we were on tour in Minsk, I met my future husband. We got married, and we had a daughter.

GREGORY: What does your daughter do?

LIDIYA : My daughter has nothing to do with theater. She studied in London, Ontario, in college, and now she’s married and living in Bermuda. My grandson was just born—he’s eight months old, actually, already nine. Every March, there’s a festival there. They invite musicians, singers, composers, and opera performers from different places, but mostly from the US and Canada. It’s an annual festival, and organizing it takes all year. That’s what she’s doing now.

GREGORY: While preparing for our meeting, I thought about you and I believe that you’ve had a happy acting career.

LIDIYA: Very much so.

GREGORY: I would say that for two reasons. First, the Taganka Theater—everyone who touched that stage carried it with them for the rest of their lives. And second, your acting career didn’t end with emigration. That’s remarkable. Let’s talk about that a bit.

LIDIYA: Have you ever heard of or met Vladimir Prokhorov, the choir director at the Russian church?

GREGORY: No.

LIDIYA: He was the choir director—may he rest in peace—at that church. He had come from Zakharov’s theater, where he was also a musical director. He was a multi-talented person, and he suggested we start putting on concerts. That’s how it all began—with concerts featuring Volodya. Not just music—I played the guitar a little and sang too. Then we started performing small scenes, and we did it regularly.

At the time, I was, of course, working—like everyone who arrives here, you have to work to survive. I worked at a store called "Arbat" in High Park. One day, a woman came in and started telling me she was looking for actors for something. It turned out to be Olya, but I didn’t mention that I was an actress—it wasn’t directed at me.

LIDIYA: Then, out of the blue, she called me. I said, "You were in my store yesterday. We talked." She said, "Oh, really?" And that’s how I agreed to be in her first play. It was "Three Novellas", with Volodya Prokhorov, her husband Valya, and me. That was the start of my collaboration with Olya. Over time, we did "Love and the Golden Book", where I played Catherine the Great.

But performances happen infrequently, and honestly, I wouldn’t have had much time anyway—I had work, and we lived far away, in Markham. Olya has her own studio, and sometimes I work with her students as a teacher. She used to have three groups—small, middle, and large. Now she has only a small group and a middle group covering a range of ages. She recently traveled to Moscow for two weeks, and I stayed to rehearse with them.

GREGORY: Does it bother you—well, I don’t want to use the word "second-rate," but the sense of some kind of limitation? Few people come to see these plays, and more importantly, a performance runs just once or twice and then that’s it.

LIDIYA: That’s fine with me. I think I’d get exhausted otherwise. I don’t know why, but if I worked in film—which I don’t really love—the filming process would suit me best. I want to perform something once and be done with it. I don’t want to repeat myself.

GREGORY: But then, what remains?

LIDIYA: Nothing remains. Why should anything remain? I don’t understand that.

GREGORY: But don’t you want something to last?

LIDIYA: No, not at all. I think it’s something from my childhood. Some people, when they grow up poor or with insecurities, work hard to overcome them and prove something. Not me. It never bothered me. I was happy at Taganka, doing what I did. And over time, I saw that people recognized my work, and that was enough for me. Olya once said, "Another talented actress wasting away here." I think that was during the "Boris Godunov" tour—maybe at a festival in England. Someone mentioned it backstage. But I don’t feel like I’m a great actress who’s wasting away. Not at all.

GREGORY: Does it bother you that in Olya Shvedova’s theater, there are only two professional actors with formal training and some level of recognition?

LIDIYA: Makes you think of Beware of the Car, right? No, it doesn’t bother me. You know, things like that only bother me if I can change them. If I choose to do this, it doesn’t bother me.

GREGORY: Okay. But do you find common ground with non-professional actors?

LIDIYA: Oh, absolutely. They work wonderfully. They’re great people—some more gifted than others—but they all try. If you go on stage worrying that someone’s not delivering a line the way you’d like, you shouldn’t be on stage at all. If your partner’s line delivery is off, then act in a way that makes it work. That’s my approach.

GREGORY: If we go back to your Taganka period and imagine that you could play any role from the productions you saw back then, what would it be?

LIDIYA: Just before I left, I was thinking about this. If he had started rehearsing "Don Juan"… what was it called?

GREGORY: "Little Tragedies".

LIDIYA: "Little Tragedies". I would have wanted to do what Natasha Tsvirko did in that. And when he told me, "Rehearse whatever you want," that’s exactly what I wanted to say. But since I knew I was leaving in a month, I didn’t say anything.

GREGORY: Well, thank you for coming. And as a farewell, I’ll say: "Rehearse whatever you want."

LIDIYA: Thank you very much.

GREGORY: I know you like other flowers—you love sunflowers, but there weren’t any. Since you recently had a birthday, and just as a thank you for being here…

LIDIYA: Thank you. I love tulips too.

GREGORY: Our guest today was actress LIDIYA BOYKO. I’ll see you next Saturday. All the best to you.